By Cindy Chin, 3 July 2025

Two years had passed since I graduated with my Bachelor’s degree in English in the US (Buffalo, New York) and moved to the Netherlands. I was at a crossroads – should I pursue a Master’s degree or a TEFL certification? I wasn’t sure what to study for my Master’s, but I had always dreamt of travelling and teaching in Asia, especially in China, where my parents are originally from.

During college, I had some experience tutoring English and I didn’t want to waste more time debating my next step. So, at the beginning of 2019 I enrolled in an online TEFL certification course while working a restaurant job with irregular hours.

What TEFL is

TEFL stands for Teaching English as a Foreign Language, and it’s a certification that allows you to teach English to non-native speakers. TEFL programmes can vary in length, but a typical certification course requires around 120 hours of training. The content includes lesson planning, classroom management, and language acquisition techniques. Many programmes are available online, making it accessible to people all over the world, and they often allow you to study at your own pace, though some set completion timelines. Costs for the certification can vary, but a 120-hour course typically ranges from €200 to €500, depending on the provider. Once certified, you can teach English in a variety of countries and continents, from Asia and Europe to Latin America and the Middle East, or even teach online.

Struggles at the beginning

I didn’t expect that two years out of school would make studying so difficult. It was my first time juggling work and self-paced learning, and I struggled to stay motivated. The course was designed to be completed in six months, but if you exceeded that time, you had to pay a €150 reactivation fee to continue. Unfortunately, I ended up paying this fee twice – spending an extra €300 – because I kept putting off my studies.

Then, just as I was thinking about teaching in China, Covid-19 hit, closing that door completely. Without travel as an option, I started looking for local teaching opportunities to stay motivated. That’s when I found on Superprof, an online tutoring platform, a Dutch student who wanted to learn English.

My first experience teaching English in the Netherlands

This student, a Dutch high-schooler, was unmotivated and frequently skipped our lessons. When she did show up, she often asked me to do her assignments for her, which I refused. Though this first experience was discouraging, it pushed me to finally complete my TEFL certification in the summer of 2020.

Shortly after, I landed my first proper job as an online English teacher for young learners in China. I taught small groups (two to four students) on weekdays and weekends, and while I loved working with them, I only taught for six hours per week, so I needed more work.

Teaching Dutch high school students online

I found another online teaching job through Indeed.nl, working ten hours a week for an after-school organization based in Hoofddorp. My role was mainly tutoring Dutch high school students via Microsoft Teams, helping them with English homework and preparing for their exams.

Unlike my first tutoring experience, these students were motivated – they needed to pass their English classes to avoid being held back a year. However, keeping their attention was a challenge. Many of them would ask to end the lessons early or got distracted by their phones.

One major challenge was the language barrier. They refused to speak English, and many expected me to simply give them the answers. Some would ask, ‘What is a verb? What is an adverb?’ – but then insisted that I explain in Dutch, a language I was still learning myself. Google Translate became my best friend!

Challenges

Looking back, my TEFL journey was not what I expected. I initially pursued it with dreams of travelling and teaching abroad, but life had other plans. Instead, I found myself teaching online in the Netherlands, facing language barriers and unmotivated students.

A few years later, I applied for an English teaching position at another Dutch after-school programme. This programme, affiliated with Erasmus University, aimed to help high school students pass their final exams and gain admission to the university. During the interview process, I was given five minutes to prepare a lesson plan before the interviewer returned and pretended to be a student. Though she praised my engaging and interactive approach, I ultimately didn’t get the position because my Dutch skills weren’t strong enough. I hadn’t realized that, just like in my previous teaching job, I would be expected to teach English using Dutch.

This reinforced an important lesson: that many English teaching positions in the Netherlands require fluency in Dutch, something I wasn’t prepared for. While I believe immersion in the target language is the best way to learn, the Dutch education system often takes a different approach. I found that fluency in Dutch was a common requirement outside of international schools.

Lessons learnt

Despite the challenges, I learnt valuable lessons:

- Self-discipline: Completing a self-paced course while working was tough, but it taught me to be persistent.

- Adapting to different teaching styles: I had to adjust my approach depending on whether I was working with young Chinese students or Dutch teenagers.

- The reality of online teaching: It’s not just about teaching – it’s about keeping students engaged, dealing with distractions, and sometimes even handling difficult behaviour.

Would I recommend getting a TEFL certification? Yes – but only if you’re truly passionate about teaching. Otherwise, it can be a frustrating and costly experience.

For me, teaching was a stepping stone. While I’m still figuring out my next career move, I’ve started gaining experience as an English editor and proofreader. My TEFL journey helped me develop skills in communication, adaptability, and perseverance – skills that I’m now applying as I explore new opportunities.

|

Blog post by: Cindy Chin |

By Paula Arellano Geoffroy, 17 June 2025

Long-standing SENSE member and Dutch-to-English literary translator David McKay won the Vondel Translation Prize in 2017 for ‘War and Turpentine’, his English translation of ‘Oorlog en terpentijn’ by Stefan Hertmans. His most recent works include ‘Revolusi’ by David Van Reybrouck, ‘Off-White’ by Astrid Roemer, and ‘The Remembered Soldier’ by Anjet Daanje.

Long-standing SENSE member and Dutch-to-English literary translator David McKay won the Vondel Translation Prize in 2017 for ‘War and Turpentine’, his English translation of ‘Oorlog en terpentijn’ by Stefan Hertmans. His most recent works include ‘Revolusi’ by David Van Reybrouck, ‘Off-White’ by Astrid Roemer, and ‘The Remembered Soldier’ by Anjet Daanje.

In the following interview, David shares with us excerpts from his life and current work, and explains how his path led him to be a renowned literary translator.

I understand that you are American but have lived in the Netherlands for many years now. Why did you decide to settle in the Netherlands?

I met my Dutch partner in the Boston area in 1994. We were in the linguistics Ph.D. programme at MIT together, but both became disenchanted with linguistic research and academia and decided to leave the programme after earning our masters’ degrees. My partner was able to stay and work in the United States for a year or so, but in 1997 she had to return to Europe. We had talked about living in Europe in the long run anyway; I had lived in Italy for a year as a child while my father was teaching at a study-abroad programme in Florence, and maybe that made the prospect of moving to a different continent seem less daunting for me. At that point I had already spent a summer learning Dutch in Leiden, so I’d already been introduced to the language and culture.

You hold degrees in philosophy, linguistics and international relations. How did your path to literary translations unfold?

Learning the language was my top priority when I first arrived here. I was enrolled in the Dutch Studies programme in Leiden for a year, mostly taking their upper-level language courses, and my partner and I started speaking Dutch to each other as much as possible. I also started reading lots of Dutch books right away and even translated one of Marten Toonder’s Tom Poes books as an enjoyable exercise for improving my language skills.

I had always had an interest in language and literature and had written plays and poems earlier in my life, so I soon began wondering whether translation would be an attractive career for me. I began taking on little editing and translation jobs and soon found myself working for Van Dale, Kluwer Law, the English Text Company and Media Monitor for short periods before finding a great full-time job at AVT, the Dutch government translation department based in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. That was where I truly learnt to translate, thanks to my experienced co-workers and the intensive feedback on my translation work that I received from them.

Meanwhile, I remained interested in literary translation. In 1999, the same year that I started working at the Ministry, I applied for approval as a literary translator by the Dutch Foundation for Literature, the Letterenfonds. I was rejected – rightly so, since I was still very inexperienced and just learning the ropes – but I received positive feedback from both the reviewer and the Letterenfonds staff and was encouraged to apply again after gaining more translation experience. In 2000, I was invited to participate in the 2000 Summer School in Literary Translation in Utrecht and Antwerp, sponsored by Dutch and Flemish literary translation organizations. I was very fortunate to learn from three great translators and teachers there: Ina Rilke, Stacey Knecht and Susan Massotty. My admiration for their work has remained undiminished over the years.

But I couldn’t combine book translation with my full-time work at the Ministry, and in the years that followed, I had only very occasional small literary jobs. By 2006, I felt I had learnt all I could from my job at AVT and was ready for a new challenge. I left the Ministry and became a freelancer, working mainly for museums and academic researchers – still two important categories of client for me today. I believe it was also around then that I reapplied for approval by the Letterenfonds as a literary translator and was accepted for both poetry and prose. Over the next few years, I had a lot of small literary translation jobs – short stories, poems and samples from books – alongside my other work, which included many book translations for museums and academics.

It was not until 2014, when I had the opportunity to translate ‘War and Turpentine’ by Stefan Hertmans, that my literary translation career really began to take off. In retrospect, I’m glad it was slow to develop; that gave me time to become an experienced, confident translator before taking on challenging book-length literary jobs. It also taught me the value of collaboration and receiving feedback on your work.

I imagine that sometimes it might be difficult to work with renowned authors. Have you experienced any of that? How do you manage those moments?

I’ve been very fortunate to work with appreciative authors who are generous with their time, and I’ve learnt a lot from their feedback on my work. I think their sensitivity to language often helps them to understand their own limitations in English and the importance of a translator’s work. But the diplomatic skills I learnt as a government translator certainly come in handy sometimes, and I must admit that it helps when you already have a successful book or two under your belt!

Early in my literary translation career, I more often encountered authors who were understandably concerned about working with a young translator who had no real track record. In one case, an author even decided to work with someone else instead – a British translator whose style was a better match for his aristocratic background. It’s easy to get worked up about incidents like that, but the lesson I learnt is that you can’t expect to be the perfect translator for every author. Instead, I look for relationships of mutual appreciation: I admire the author’s work, and the author values my work. That lays a firm foundation of trust and respect on which we can build.

No matter what kind of translation I’m doing, I’ve learnt that I can avoid a lot of awkwardness through clear communication with clients and authors. I take the time to learn what’s important to them about the project, their priorities and concerns, and it reassures them to know that I’m genuinely interested in what they do and seek to understand the larger context for my work. And when I ask an author detailed questions about the book I’m translating and then take the time to reply to their own questions and comments in detail, they understand that I respect their work and value their contribution to my translation process. But that doesn’t mean I accept their suggestions uncritically – I expect the same respect for my expertise as a translator. I’m sure this collaborative approach is one reason for the success of some of the books I’ve translated.

Do you have favourite current or past projects? What made them special?

In recent years, I’ve taken the initiative to pitch a number of books to publishers. This is a demanding process and often doesn’t lead anywhere, even when you’re an established literary translator like me, so I’m not sure I would recommend it to anyone. At the same time, it’s wonderful to know that a few books I love have entered the English-speaking world through my efforts. Some only reach a small group, like J. Slauerhoff’s Dutch adventure classic ‘Adrift in the Middle Kingdom’, which failed to attract much critical attention despite being the runner-up for the Vondel Prize. Others find their way mainly to specialists, like ‘We Slaves of Suriname’ by Anton de Kom (another Vondel runner-up), which inspired thoughtful, enthusiastic articles in academic journals. In contrast, Anjet Daanje’s ‘The Remembered Soldier’, which has just come out in the United States, has received rave reviews in The Wall Street Journal, Publishers Weekly and elsewhere, and seems set to reach a large number of readers. But whatever happens to my passion projects out there in the world, I love them all equally.

Translating for the theatre is also a special thrill because of the collaborative nature of the work and the chance that you might see your words spoken by actors on stage. Working with playwrights, actors and directors has taught me a lot about staying playful, creative and open-minded.

Finally, I love mentoring emerging translators and always learn a great deal from it myself. It creates a personal bond, and I continue to follow the careers of my mentees with excitement and interest. Some have also become good friends.

We are in a particular moment in history in which AI is present in almost every aspect of life. What is your take on AI and translations? Do you use it? Are you worried in some way?

I don’t think AI will replace literary translators any time soon because, like neural machine translation, it’s based on the AutoComplete principle: it searches for the most likely word in a given context. That sometimes works well enough if you want bland, generic prose, or prose in some kind of well-defined pre-existing style, but it can’t capture a literary author’s original, idiosyncratic, creative stylistic choices simply because of their newness: nothing like them was in its training data. And at least for now, Machine Translation Post-Editing (MTPE) and other AI-assisted forms of translation are a dead end in the literary world. It often takes as much time to revise an AI literary translation properly as it would to translate the book yourself, and the result is inferior because seeing the AI version can dampen your own creativity and get in the way of reading the original properly. Psychologists call that a priming or anchoring effect.

On the other hand, publishers may find that AI can play a role in the translation of predictable genre fiction, which probably sells better than literary fiction anyway! And of course, literary translation, like so many other creative endeavours, never paid very well anyway, so most literary translators combine it with other types of work in order to make a decent living. In the translation that I do for museums and academics, I see no real alternative to investigating whether AI-based tools can help me to do my work more efficiently while offering at least the same high level of quality. I share the ethical objections to these systems (such as violations of copyright and privacy, unsustainable consumption of energy and the political role of tech companies in the United States), but I don’t think the solution is for translators to shoot themselves in the foot by refusing to adopt the technology that the rest of the world is using. I do believe in supporting professional organizations, like the Authors Guild in the United States and Society of Authors in the UK, that are joining the effort to hold AI companies responsible for their massive theft of copyright-protected works for AI training purposes.

I believe the translators into English who survive and thrive in the years ahead will set themselves apart by specializing, communicating clearly, working closely with direct clients and listening carefully to them, networking both online and in the real world, making intelligent, discerning use of the best possible translation tools, and putting quality first. (And that’s not just me patting myself on the back – I’m an introvert and really have to push myself to do real-world networking, for instance!)

If you could offer some tips to students or language professionals willing to take on literary translations, what would you say?

1. Don’t do it for the money! Think carefully about your financial needs and build up your literary translation activities slowly, making sure at every step that they’re not endangering your ability to provide for yourself adequately. Reach out to experienced translators to find out about typical rates and other professional practice issues, so that you find the sweet spot between underselling yourself and making unrealistic demands based on your experience with more lucrative varieties of translation.

2. Connect with other literary translators through organizations like the Dutch Foundation for Literature, Flanders Literature, the American Literary Translators Organization, and the Translators Association at the Society of Authors. Join mailing lists and other online groups for literary translators such as ELT, ELTNA, and World Kid Lit.

3. Take the time to read widely in both Dutch and English, and check out book reviews and literary magazines as well. This will give you a better sense of the two literary cultures and where you may fit into them.

4. Take your time before applying to become an approved translator. I was lucky enough to be allowed a second try, but some translators aren’t permitted a second chance. Make sure the sample you send to the Letterenfonds or Flanders Literature really is representative of your best work, pick a book that showcases your skills but isn’t unduly challenging, and accompany your translation with a brief message for the reviewer explaining the trickiest choices you made.

5. When you do literary translation, take your time. If you like to dash through the first draft, that’s fine, but that means you’ll need to spend even more time checking and polishing your work afterwards. Most literary translators do many rounds of revision. You need to do at least three: one to check whether you’ve caught all the nuances of the original, one to see whether the translation stands up as a piece of English writing in its own right, and one or more final checks (probably machine-assisted) for spelling, stylistic consistency and mechanics. But that’s a bare minimum! And if you’re translating a book for publication, you can expect it to come back to you several more times with comments from the author, one or two editors, the proofreader, and who knows who else… (See point 1: Don’t do it for the money!)

6. Ask questions when you don’t understand things. If you’re afraid of looking silly, don’t go straight to the author – first, ask a friend, family member or acquaintance, preferably one who’s an insightful reader and would appreciate the piece of writing that you’re translating. If they can’t figure out the answer either, then it’s probably not a silly question. But when you do get in touch with the author, please be friendly and diplomatic and make sure your questions don’t sound like veiled criticism of the writing. Meanwhile, you may want to take the opportunity to get to know the author better. That’ll give you better insight into the writing, and it’s great networking.

Do you read for pleasure as well? What are you currently reading?

I don’t think you can succeed as a literary translator without being an avid reader. I read a great deal purely for pleasure (right now, I’m alternating the Cadfael mysteries by Ellis Peters with a variety of other books) and often mix business and pleasure, in what is no doubt an unhealthy way, by reading a lot of books that feed into whatever literary translation I’m working on. For example, while working on ‘The Song of Stork and Dromedary’ by Anjet Daanje, I read many of the books that were on her own reading list as she wrote the novel (you can find that list on her website). That includes many books by and about the Brontë sisters, but also Margaret Atwood’s ‘Alias Grace’ and Carlo Rovelli’s ‘The Order of Time’. I also occasionally mix work and leisure in a different way by flipping through art books in the evening – staring at Van Goghs or Monets can be very restful after a long day of word processing.

|

Blog post by: Paula Arellano Geoffroy |

By Claire Bacon, 2 June 2025

It’s no secret that many language professionals are facing challenging times. Whether it’s the rise of AI, withdrawal of National Institutes of Health funding, or university budget cuts, many of us are reporting that we have far less work to do than we did in recent years. One way to adapt is to learn from each other by sharing our experiences.

Towards the end of 2024, I lost two major clients. With no notice, the medical journal I worked for decided as ‘part of a broader strategy to streamline workflow and enhance external capabilities’ to no longer contract external copy editors and, thanks to the massive university budget cuts in the Netherlands, I suddenly lost teaching work from a Dutch university. This left some big gaps in my work schedule – not something I have been used to in the last few years. Instead of panicking, I decided to keep calm and carry on. I asked myself two questions: how can I adapt to this changing situation and how can I use this extra time to my advantage?

Adapting to the changing situation

My immediate challenge was to find new clients to fill the gap. Luckily, I had strategies for this that have worked well for me in the past. I built up my original client base through content marketing – writing blog articles about research writing and sharing advice on social media. I had neglected my blog for a few years because I simply didn’t have the time for it – there was always plenty of work to do and of course the family needed attention. Now was the time to reignite it. I dusted off my list of ideas for blog posts and got back to work. I realized just how much I enjoyed creating content to help researchers with their writing, and was almost thankful to my current difficulties for forcing me back into blogging!

I also developed an effective strategy for content marketing on social media. Although I have done this in the past, I did find it difficult to maintain a consistent online presence in the face of work and family commitments. To improve my chances of success this time, I decided to stick to one social media platform (I picked LinkedIn as this is where I have the most useful interactions with like-minded professionals and potential clients) and to make a content marketing schedule. A very helpful discovery here was the scheduling function on LinkedIn, which allows you to prepare posts in advance and schedule when they will be published. This allowed me to spend one or two quiet working days preparing my LinkedIn posts for the next month, rather than stressing out finding the time each day to post. I also allotted 15 minutes each day to going through my LinkedIn feed and interacting with others. These marketing efforts have already brought in new work.

Diversifying: Using ‘unwanted’ extra time to our advantage

Although no freelance language professional wants gaps in their schedule, I knew there must be ways to make the most of this extra time. I briefly considered a complete career change and getting new qualifications, but realized that I do still have a decent client base and that I love editing and teaching scientific writing too much to throw in the towel just yet. Then, a lab in New York got in touch out of the blue asking for scientific writing workshops, which gave me the motivation I needed to pursue this avenue of work independently. I started working on developing my own scientific writing courses and have now added this as an additional service on my website.

We all know that AI is affecting our work as language professionals and that we need to embrace AI to move forward. So, to learn more about AI, I signed up for the Academic Language Expert’s free AI bootcamp and invested in Emma Nichols’ AI in Medical Writing and Editing course . Both were very informative and I now know a lot more about AI and how to use it. However, I confess that I am still struggling to actually use AI myself in my editing and writing. I have spent many years developing my writing and editing skills and have approaches to writing and editing that work well for me. I am also concerned about the effect of AI on critical thinking skills in young researchers if they start to rely on it for their writing rather than using it to facilitate the writing process. I’m looking forward to getting more insights and advice on this at the SENSE Jubilee Conference in June!

What else to do with this extra time? I realized I could improve my German. I live in Germany and my German is already good; I get by in most situations, I have close friends with whom I speak only German, and I can happily read novels in German. But I have been stuck at a B2-plus level for a while now and realized that I cannot get to C1 level by myself. Now I had time to do something about it, and enrolled for a twice-weekly intensive online course. This course highlighted some specific language-learning goals for me this year: to improve my grammar and expand my vocabulary. I have vowed to read more in German this year to help achieve this (so far I have three novels under my belt). I would not have set these goals if I hadn’t lost my clients.

Staying positive

These are challenging times, but we language professionals still have a valuable service to offer our clients. I would love to hear about how you are responding to these challenges, so do drop me a line! I am also looking forward to chatting with you all at the conference in June.

|

Blog post by: Claire Bacon |

By Paula Arellano Geoffroy, 19 May 2025

The Encyclopedia Britannica explains that interest groups are a natural outgrowth of the communities – people with common interests living in a particular area – that exist in all societies. ‘Most interest groups are not formed for political purposes. They usually develop to promote programs and disseminate information to enhance the professional, business, social, or avocational interests of their members.’

The Encyclopedia Britannica explains that interest groups are a natural outgrowth of the communities – people with common interests living in a particular area – that exist in all societies. ‘Most interest groups are not formed for political purposes. They usually develop to promote programs and disseminate information to enhance the professional, business, social, or avocational interests of their members.’

SENSE currently has ten Special Interest Groups (SIGs) that meet in person or online and whose meetings are open to all members. Guests are welcome to attend one or two meetings before deciding whether they would like to join SENSE.

This week, I invite you to meet the Amsterdam SIG and its conveners, Tina Manousakis and Samuel Murray.

The Amsterdam SIG experienced a revival last year thanks to you both. Can you tell us a bit about where you are from and about your backgrounds?

Tina: I came to Amsterdam eight years ago from the US, though I also hold Greek citizenship. I am a self-described ‘lovepat’. I moved here for my partner, who is Dutch. I have been a lurking member of SENSE since I first got here.

Samuel: I’m an English-Afrikaans freelance translator, originally from South Africa. I’ve been a member of SENSE since around 2016, and I’ve served on SENSE’s Executive Committee (EC) as Web Manager (four years) and interim Content Manager (one year). I have a Dutch wife and two children aged 22 and 23.

How did you hear about SENSE and why did you decide to join?

Tina: I was surfing the internet for English language jobs and came across the website. Since I am not a translator, but rather an English trainer, I emailed SENSE and asked if it would be OK to join. After I was told that there were other English language teachers, I joined so that I could find a community.

Samuel: I believe I have known about SENSE since around 2010, but did not join because I’m not a native speaker of English. I can’t remember what prompted me to join.

What made you volunteer as Amsterdam SIG conveners? Are you enjoying the experience?

Tina: Samuel asked me to help out, and being part of the organizing team of a group is something I am pretty comfortable with. It’s been great fun so far.

Samuel: As an EC member I was in a position to assist Alison Fisher (the previous convener) with recreating the Amsterdam SIG. I originally said that I would help organize only three or four meetings, on the assumption that two other Amsterdam members would step up as conveners. Tina volunteered at the first meeting. I think Tina and I make a good team, however, and I’ll likely continue to help organize the SIG meetings for the foreseeable future. I’m fortunate in that the SIG kind of runs itself – since our meetings don’t have a CPD component yet, there is very little to arrange except making sure that all the Ts are crossed.

I believe you usually meet once a month at the Stadsbar on the 7th floor of the Amsterdam Public Library. What are the main topics you bring to the table?

Tina: There are no topics as this is an informal chat environment and we have talked about everything from our professional experiences to current events and books.

Samuel: The Amsterdam SIG meetings are currently informal get-togethers, so we end up discussing literally anything. Sometimes the discussions are language-related but sometimes they are culture-related, and sometimes they relate to an experience that one of the attendees had.

What can people expect when they join you at the Stadsbar?

Tina: Food, drink, and scintillating conversation of course.

Samuel: We’re a group of people who share an interest in language work. We enjoy learning about each other’s lives and experiences. There is a small selection of beers and wines and some food is served from the kitchen until around 19:00.

Are you good readers? Can you recommend us something interesting?

Tina: I am currently reading a Da Vinci Code-esque adventure called ‘The Medici Return’ by Steve Berry. It’s early days but I am enjoying it. The last book I read was ‘I Hope This Finds You Well’ by Natalie Sue. If you like workplace angst fiction, then this one’s for you. And for high fantasy fans, I also recommend ‘The Deverry Cycle’ by Katharine Kerr. I am only on book 5 out of 16 but am loving the themes in the series so far.

Samuel: I currently have two books in my bag when I’m on the train: a little coming-of-age gem by Patrice Villalobos called ‘Une jeunesse’ and an interesting tome by Hans Melissen and co-conspirator called ‘Iedereen rijk’ about money from heaven.

|

Blog post by: Paula Arellano Geoffroy |

By Christien Ettema, 5 May 2025

Image created with the free version of Dall-E in ChatGPT, based on my off-the-cuff prompt: ‘Please create an image of the frenemy concept applied to AI, where AI can be a student's best friend but also an enemy to their motivation and learning’

Image created with the free version of Dall-E in ChatGPT, based on my off-the-cuff prompt: ‘Please create an image of the frenemy concept applied to AI, where AI can be a student's best friend but also an enemy to their motivation and learning’

Since the launch of ChatGPT in November 2022, educators around the world have been struggling to formulate adequate guidelines for the use of Generative AI (GenAI) tools by students. The challenge is daunting: how can we safeguard assessment when students can use GenAI as a shortcut to do their homework and write their thesis reports? How can we ensure that students continue to engage with content in a meaningful way and develop critical thinking and problem-solving skills? How can we keep up with all the new AI tools and deal with the growing integration of AI into common software?

One thing is clear: the brief time that teachers could simply forbid students from using AI tools is past and gone. According to a recent UK survey, student use of AI has exploded, with nine out of ten UK undergraduates now using AI for their assignments. From my experience at Utrecht University, where I teach academic writing to undergraduate and PhD students, I can see that the situation in the Netherlands is no different; and like other teachers, I’m struggling to keep up.

Thus, I was keen to attend the UniSIG Zoom meeting on 7 March to hear Peter Levrai from the University of Turku, Finland, share his ideas on how university teachers can encourage students to engage with AI in a positive way. Peter’s talk was based on a blog post he and his colleague Averil Bolster recently published on the topic, based on their own experiences in the classroom. I’m summarizing the main points of his talk here. Note: Peter’s talk focused on the use of generative AI tools such as ChatGPT, which I will refer to here simply as ‘AI’.

To frame the issue at hand, Peter used the term ‘best frenemy’ to capture both the opportunities and threats that AI poses to student learning. AI has the potential to make life much easier for students, but it can also undermine their motivation and opportunities for learning and lead them down the rabbit hole of disinformation. Drawing on Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives, Peter argued that AI can speed up lower-level tasks such as listing, summarizing and applying, but cannot and should not replace higher-level tasks such as creating, evaluating and analysing. The arrival of AI tools means that students will now have to operate (or learn how to operate) at these higher levels of thinking more consistently.

Next, Peter pointed out the problem with guidelines that define ‘how much’ AI can be used for different assignments. These guidelines date back to the very recent time when students had to actively seek out AI, but with the explosion of tools and intrusion of AI into mobile phones and common software, it has become almost impossible to avoid AI; it is simply everywhere. Therefore, rather than focusing on ‘how much’, it makes more sense to focus on identifying ‘why’ and ‘how’ students are using AI and, based on these insights, to develop strategies that encourage AI use that has the best outcome for student development.

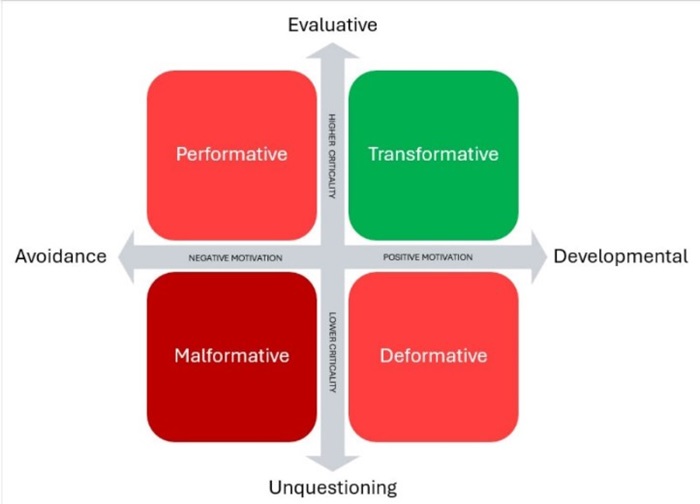

The AI Quality of Engagement matrix (AIQEM) developed by Levrai and Bolster (2024)

The AI Quality of Engagement matrix (AIQEM) developed by Levrai and Bolster (2024)

Combining the qualitative dimensions of ‘motivation’ and ‘criticality’ into a matrix provides a framework for assessing the quality of student engagement with AI tools. As the diagram shows, there is really only one desirable outcome: that students use AI to develop and test their ideas (positive motivation) and carefully evaluate the quality of the AI output (higher criticality). The diagonal opposite is obviously the worst case (using AI as a shortcut and taking the output at face value), but the other two options are only slightly less worrying: even if the motivation to use AI is positive, using AI output without further critical analysis undermines development and learning; and using AI as a shortcut while adapting the output just enough to pass it off as one’s own is equally questionable.

Based on this analysis, Peter argued that the main concern for teachers should be to help students better understand how they can use AI to develop their knowledge and ideas in ways that enhance rather than undermine their learning. Good strategies include using AI to brainstorm ideas and develop background knowledge on a topic, and asking the chatbot to give feedback, act as a tutor, or be a debate partner. The key is to develop good prompting skills. For example, Peter suggested trying different verbs (comparing output from asking to explain a topic versus to debate a topic) and using persona prompts, where the chatbot is given a highly specific role (see Valchanov, 2024). I’m also thinking of the various prompting frameworks already out there, such as the RISEN framework (Role, Instructions, Steps, End goal, Narrowing) that is now embedded in ChatGPT.

A second conclusion drawn from the matrix is that students need to understand the limitations of GenAI output and, now more than ever, must develop critical evaluation skills. Finally, Peter added that the matrix can also inspire us as teachers to reflect on our own use of AI, to explore how AI can support our professional development, and to increase our understanding of the challenges our students are facing.

In closing, Peter emphasized that, with the arrival of AI tools, our own thoughts, imagination and creativity are more important than ever. We should also not give up on learning and teaching lower-order thinking skills because without these skills we cannot successfully operate at higher-order thinking, nor can we interact with AI output in a meaningful way. Last but not least, we need to make students more aware of issues such as data ownership and security, and encourage them to check that AI works for them, not that they work for AI.

After Peter’s thought-provoking presentation, the following lively discussion ensued:

Joy: When you encourage students to use AI, do you ask for transparency?

Peter: Absolutely. For assignments, students have to submit a statement disclosing their use of AI; they are also advised to keep a history of their interaction with AI so that they have proof of their own input in case AI detection software flags their work.

Michelle: How useful would it be to discuss ethics in relation to AI use among students?

Peter: Hugely important. And we also need to talk about how the harvesting of training data violates copyright and privacy, the trauma of people who have to clean up the AI data that feeds the models, the tragedy of the commons where we have to use AI or be left behind, and make students aware that everything that you put into these tools is owned by the companies behind these tools. See Stahl and Eke’s recent article in Elsevier.

Wendy: Do you see a difference in AI use in terms of practice and appropriateness by students at different levels, e.g. PhD vs. MA or undergraduate? It seems to me that the higher the level, the less helpful or the more careful one must be, even with positive motivation and high criticality.

Peter: My focus is mostly on undergraduates, but what I see is that AI use is not a matter of academic level; it is partly faculty related (arts vs. sciences) and it also varies a lot between individuals, with some students using AI for everything and others staying away from it for a variety of reasons. But generally speaking, the higher the academic level, the more work has to go in to getting something useful out of GenAI.

Jackie: How can teachers ‘check’ what students have done with AI?

Peter: The submission statements and self-policing are important here, but we cannot check how honest they are. At some point, schools will have to accept that these tools are being used. My main concern is that students will get stuck in superficial analysis, the dumbing-down effect of just reading AI summaries of articles and not fully engaging with original texts, which will impair reading and writing skills. The utopia is that AI will do all the dirty work so that we will have time to write poetry. But no, we’ll just watch more Netflix. Forming our own thoughts, opinions, creativity, that’s where humans come in.

Tom: I’m a corporate trainer, not a teacher. The participants in my report-writing workshops are often consultants. They are using AI within a company-protected AI environment for different stages in the writing process, from ideation to crossing t’s. What is your take on the speed of development of AI. How long will report-writing workshops be necessary…?

Peter: I’m optimistic, as long as we can adapt. The fundamentals won’t change. To draw a parallel with using AI for coding: you still need to understand how the code works to be able to fix problems and debug code. Similarly, you need to understand how text works, how writing works, how people read, to be able to interact with AI output and produce a good end result.

Charles: If a PhD student uses AI to help with a research paper, can this impact the ‘publishability’ of the manuscript? For example, are there concerns about potential loss of advantage if a research design in a highly competitive field is plagiarized before the original manuscript is published?

Peter: I would be very cautious about putting anything into an AI that is confidential information. Ownership can be lost as soon as you put it into an AI. Depending on the terms and conditions of the tool, your work may be lost – even if tools claim they will not use your data for training, even if you have a paid version. A solution would be to have a safe and secure ‘in-house’ AI system, but at this point that is a significant investment.

References

Levrai, P. and Bolster, A. (2024). Supporting ethical and developmental AI use with the AI Quality of Engagement Matrix. Theory into Practice Blog.

Lewis, B. (2019). Using Bloom’s Taxonomy for Effective Learning. ThoughtCo.

Stahl, B.C. and Eke, D. (2024). ‘The ethics of ChatGPT – Exploring the ethical issues of an emerging technology’. International Journal of Information Management, Vol 74, 102700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2023.102700

Valchanov, I. (2024). Best ChatGPT Prompts: Persona Examples. Team GPT.

|

Blog post by: Christien Ettema |

By Paula Arellano Geoffroy, 25 April 2025

Freelance interpreter and instructor Annabelle Saucet (LinkedIn: annabelle-saucet) joined SENSE in January. She is currently based in Hoorn, the Netherlands. I invited her to share a bit about her interesting story, and here’s what she had to tell.

Can you tell us about your background and where you are from?

I’m British, born in London. Having grown up in a multicultural family, some of whom visited regularly from different continents, I’ve been exposed to many cultures from a young age. I’ve loved learning languages since then and, being very pragmatic, I pursued translation studies. I then chose a career that allowed for travel, language learning, social connections as well as cultural immersion and exchange: teaching English. This led me to all the other professional opportunities I’ve had, and I am so grateful for them. My current adventure is here, in North Holland.

Why did you decide to settle in the Netherlands?

I’ve got to be honest, I came here for love… and my husband is here for work. Moving to North Holland was a good career move for him, so here we are! As a couple, we’ve lived in England, France and Japan before. We’re no strangers to the expat life. We’re happy here. My impression of the Netherlands so far is that it is a well-developed and structured country with a rich history, and friendly people. I can’t wait to keep improving my Dutch and continue learning about the culture and people here.

What kind of projects have you worked on?

I’ve worked as a language teacher (EFL), a bilingual teacher trainer, a translator and interpreter (French-English), and a Montessori guide.

My passion is learning, and creating meaningful experiences. Andragogy and pedagogy fascinate and inspire me, as does culture. I love living abroad because life is full of challenges, discoveries and interesting connections. I believe that being surrounded by other cultures enriches my journey of self-improvement, brings new and fascinating things to learn about, and challenges my own stance and perspective.

How did you arrive at interpreting as a profession?

I’ve always wanted to use my skills to make a contribution to the world. As a teacher or trainer, I would strive to create meaningful learning experiences. As an interpreter, I believe I am choosing a practical and impactful way to contribute by facilitating exchanges to ensure connection and understanding.

Since the move to the Netherlands, I remain practical and realistic. My language pairing is French-English, and I no longer live in a French or English-speaking country. I cannot deny my passion for learning, so I am also open to opportunities in education, learning and development, anywhere I can draw on previous experience, transferable skills, and a well-set desire for my work to be meaningful and impactful.

What do you enjoy doing in your free time?

Dance! Movement to music will always put a smile on my face. Currently, Zumba and step class, although I’d like to return to Cuban salsa, and try jive rock. I also enjoy exploring new places, dressmaking, meditation, Iyengar yoga, board games, studying Dutch and Italian, and maintaining my French.

Where did you learn about SENSE and why did you decide to join?

I most likely started with Google, the beginning of many searches. Community is really important, especially when living abroad. If you think about your favourite colleague or friends, you’ll remember that your relationship with them coloured your experience of wherever you lived/worked. People don’t stay in a job if they have terrible colleagues, or at any class if they don’t like the instructor. Social connections make or break any experience, and as I am settling here, I hope to find people I can truly connect with.

|

Blog post by: Paula Arellano Geoffroy |

By Tiffany Davenport, 10 April 2025

The AI takeover

It’s 2025, and the list of jobs already being replaced by technology is pretty mind-blowing. Self-checkout machines are replacing cashiers, chatbots are replacing call center agents, and automated robots are replacing warehouse workers.

There are AI surgeons and radiologists, agricultural drones, 3D printers, and automated tools for accounting, video editing and graphic design – plus self-driving trains and subways… it’s a lot.

Then there’s AI-powered writing software taking over copywriting and translation jobs. I can grasp industrial robots building cars, scanning my groceries and even delivering my packages. But I can’t grasp AI being a better writer. How is that possible? I imagine it’s just been fed loads and loads of writing samples and guides – maybe everything ever written (?) – and it uses some robot logic with nouns, verbs and adjectives that lets it rebuild sentences, themes and stories. Yes, actual stories! I hate it for making my job look easy and taking away my billable hours, but I’m also fascinated by it.

My relationship with ChatGPT

Last autumn, I typed into ChatGPT: I’m sad.

‘Why?’ it asked.

‘I’m a copywriter, and you’re taking my jobs…’

ChatGPT typed back: ‘Awkward…’

Just kidding.

What it did do was offer me tips on how to position myself as a copywriter in the AI era. It suggested I market myself as a copywriter who uses AI as a tool, emphasizing its accuracy and efficiency alongside my human eye and experience. I took its advice. I pitched myself as a hybrid copywriter who offers human creativity and AI efficiency. I highlighted my 20-year career as a copywriter and my expertise in brand voice comprehension, strategic vision and elegant storytelling.

I went on to laud AI as a remarkable tool but explained the setbacks…

Your brand's written content is its voice to the world. You can’t just leave that to AI alone. It will miss specific opportunities for connection and it will make mistakes, and whether we’re talking copyright infringement or just plain misinformation, those mistakes can be very costly and embarrassing.

It’s true! Even ChatGPT has a disclaimer at the bottom of its page: ‘ChatGPT can make mistakes. Check important information.’

Then I threw in my personality… AI doesn’t have one of those. Right?

To know me is to know I overthink everything – but as a copywriter, that’s good. I will overthink and approach your brief from every angle. I will prompt AI with dozens of questions before I find the best and most concise way to tell your story, then I will work in the flow with the right balance of empathy and humour.

As I’m writing this, I wonder: can I prompt ChatGPT with a personality?

Me: ChatGPT – What are some machines that have replaced humans in the workforce, and can you respond as if you were a drag queen?

ChatGPT:

Moving on…

We’ve had our ups and downs

Last year, I had to write for a Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A) firm, which meant diving into some pretty nitty-gritty text for their website. The problem? I didn’t know much about M&A, so I turned to ChatGPT for help. I typed in a few different prompts to get a wide range of answers and educate myself on the terminology. Then, I cross-referenced that information with their old website and notes from my visit to their office in The Hague. I pulled it all together to create copy that was concise, accurate and personal. ChatGPT actually helped me become a better copywriter. And that got me thinking: What other new areas can I write for? The possibilities are endless.

Sometimes I run a grammar check on ChatGPT, and without me asking, it will rewrite a sentence. A perfect sentence, a beautiful sentence. It crushes me. I won’t use it. I take part of their suggestion, reword it and rewrite the whole paragraph if I have to just to make it as beautiful in my own voice. The goal is to beat the machine.

More than just a writing tool

What else does this thing do? Well, pretty much everything. I’ve found new recipes, analysed my dreams, read the latest on hormone replacement therapy and even gotten help with my creative writing. While applying for funding for a short film I wrote, I ran a grammar check on ChatGPT ‒ then, out of curiosity (or exhaustion), I asked what it thought of my script. The way it broke down my character arcs and pushed me to get more out of a scene was incredible. I mean, scary, yeah… but also incredible. And ChatGPT always offers encouraging words. So sweet! Wait, are we friends now?

ChatGPT:

Going forward

Whether I’m writing for an agency or translating for a production company, it’s the little human touches that the clients always notice. My copy has to connect and sometimes it’s one cute little word that does the trick. It's also important to be aware of cultural nuances and how language evolves. I try to stay up to date. I follow the right influencers, I watch the right films, and while I do know about Gen Alpha, I also know that I can’t get away with using rizz in a sentence. That’s just cringe. I can barely get away with using cringe.

It’s all about striking a balance. As great as ChatGPT is, I don’t think it can manage that like I do. But not every client cares about that balance. ChatGPT is amazing and it’s free. It will continue to undercut my work and that sucks. What else can I do? I love scriptwriting, but breaking into the industry – let alone making money from it – is tough. Teach English? Feed an AI machine for a very low rate? I like my feet. There’s an OnlyFans for feet, right? I wonder what it pays? Oh wait, I’ll ask ChatGPT…

ChatGPT’s review of this post.

ChatGPT’s review of this post.

|

Blog post by: Tiffany Davenport |

By Sally Hill, 31 March 2025

If I told you I was a scientific writer who writes non-clinical study reports, would you know what I mean? I suspect that many in-house language professionals have jobs we’d never heard of in school when considering careers; jobs that are so niche you roll into them without noticing after working elsewhere. For me this involved working first as a genetics researcher, then as a biology teacher, and finally as a freelance medical translator, manuscript editor and lecturer in scientific writing.

These days I work at a small Dutch biotechnology company where my work helps to get cancer drugs approved for use in patients. Most of my day-to-day work involves talking with scientists about their results, then putting a story about their data down on paper as clearly and accurately as possible in what’s called a non-clinical study report. But I’m also involved in answering questions from regulatory bodies relating to reports I’ve written; in writing manuscripts; in organizing internal speakers for monthly research overviews; I’m helping develop a company-wide style sheet; and I’m in an IT workgroup that’s testing Microsoft Copilot (ever heard of large language models and AI tools? anyone?).

What’s a non-clinical study report?

Non-clinical study reports are technical reports that biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies and contract research organizations (CROs) use to document the results of their experiments – some experiments are done in cell culture in the lab, and others in animal models. These experiments – and the accompanying reports – are needed in the pre-clinical phase of drug development to persuade regulators that the drug is safe and effective before testing starts on humans in clinical trials.

I’ve recently started to give a three-hour workshop on non-clinical study reports as part of the professional development programme of the European Medical Writers Association (EMWA), together with another writer whom I met through EMWA. But I don’t consider myself an expert. While I’ve been writing study reports for ten years, I’ve not been able to find any external training or resources on how to write these reports.

Want something done? Do it yourself!

I went to my first EMWA conference back in 2021 and I was looking forward to getting some training in my particular niche of ‘medical writing’. But all of the sessions were related either to medical communications or to clinical trials. None of the talks or workshops were about non-clinical studies, and certainly not about how to write reports on them. After hearing about my disappointment, a long-time member suggested I simply give a workshop myself, and gave me the name of someone to contact who might be able to help.

Luckily the other writer had some experience in giving EMWA workshops and in writing non-clinical study reports, so a new EMWA workshop was born. Imposter syndrome – yes that familiar beast – keeps on raising its ugly head, but it’s quieter than it used to be.

Lessons learnt

So while I should long be past the stage of deciding what I want to be when I grow up, I think I might actually finally know: a scientific writer! This job and my volunteering for EMWA (and SENSE) have brought together my loves of science, language and knowledge-sharing. If any of you talk to teenagers wondering what subjects to choose or what career path to follow, just tell them to stick with what they enjoy. After all, if you enjoy something, you’re more likely to succeed at it. It’s worked for me anyway.

|

Blog post by: Sally Hill |

By Anne Hodgkinson, 17 March 2025

In the Netherlands, one sign of spring as reliable as hay fever is the announcements of performances of J.S. Bach’s ‘St Matthew Passion’ in the weeks before Easter. Whether it’s the local choral society or the country’s top choirs, it seems everyone puts one on. You’ll see other passions and composers, but the St Matthew is the most frequently performed by far. The fact that this is the appropriate time of year liturgically (Jesus was crucified and died on Good Friday) partly explains the timing. However, there are more performances of it in the Netherlands, in both per capita and absolute terms, than anywhere else in the world, even in Bach’s native Germany. On average there are about 200 performances here every year, compared to only a few in, say, Germany. What is going on?

The tradition began with reciting the Gospels on Good Friday. (The medieval ‘Passion play’, one of the mystery plays, is a secular offshoot whose descendants include the hit musical ‘The Passion’ and ‘Jesus Christ Superstar’.) Over the centuries, simple chant became more polyphonic, that is, having more than one vocal line at once, then added instruments, and by the Baroque period the standard forces had expanded to choir and orchestra, plus soloists including a narrator (the ‘Evangelist’) and Jesus. Bach’s St Matthew Passion is a masterpiece. First performed in 1727 in Leipzig, presumably on Good Friday, it is big, employing two choirs and two orchestras plus vocal soloists, and it usually lasts at least three hours. Bach weaves the story through a huge range of emotions and colours in chorales, choruses, arias and duets, giving it a dramatic power verging on the operatic.

For some Christians it is a consummate religious experience. They can experience Jesus’ suffering vicariously and have moments for reflection in the chorales (hymn tunes; Bach’s audience would have sung along with them). The piece ends solemnly with Jesus’s burial as the grief-stricken choir – unaware he’ll be resurrected in three days – wishes him ‘Ruhe sanfte, sanfte Ruh’ (‘gently rest’). Applause is often considered inappropriate after church performances. Martin Luther is on record as expressly disapproving of acting out the Passion ‘in words and pretense’, since both complicated polyphony and sheer beauty would distract attention from the message. Christians, he felt, should experience Christ’s suffering in real life. (He’d be rolling in his grave listening to this music!) Nevertheless, Protestants and Catholics alike kept the Passion oratorio as part of their Good Friday liturgy. Bach’s piece uses the Luther Bible as a basis, compatible with the Dutch Reformed Church’s mix of Calvinism and Lutheranism.

For the non-religious, St Matthew Passion is also sublime both as drama and as music. Its depth of feeling is something many people don’t associate with Bach, whose ingenious counterpoint is sometimes considered too mathematical to tick any emotional boxes. It has an amazing diversity of melody, harmony, flashy passages, poignant moments and some stunning effects, like the shimmering strings that always accompany Jesus when he sings, like a sonic halo, to name just one. It’s full of details; you can listen to it over and over and find something new every time.

For the non-religious, St Matthew Passion is also sublime both as drama and as music. Its depth of feeling is something many people don’t associate with Bach, whose ingenious counterpoint is sometimes considered too mathematical to tick any emotional boxes. It has an amazing diversity of melody, harmony, flashy passages, poignant moments and some stunning effects, like the shimmering strings that always accompany Jesus when he sings, like a sonic halo, to name just one. It’s full of details; you can listen to it over and over and find something new every time.

It’s indisputably great music. So why don’t other countries put it on as much as the Netherlands? I think the answer is a confluence of several factors in addition to sheer excellence: the ‘Mengelberg tradition’ and its opposition; the strong Dutch choral presence and a good Lutheran ‘fit’; the early music movement; and the fact that the original language isn’t a problem for the Dutch.

After Bach’s death in 1750, his music was largely forgotten. The St Matthew Passion was not performed again until 1829. The composer Felix Mendelssohn conducted a choir and orchestra of hundreds (Bach may have used 50 or 60), at the time appropriate for such a monument, and made drastic cuts to the score, including two-thirds of the arias. Today these adaptations would be unconscionable violations of the composer’s intentions, but despite or perhaps because of them, the concert was a hit. The first performance in the Netherlands was in 1870 in Rotterdam. In 1899, Willem Mengelberg conducted the piece with the Concertgebouw Orchestra and Toonkunstkoor Amsterdam in The Concertgebouw for the first time. Their annual Palm Sunday concerts became so popular they were even broadcast live on the radio.

In a recurring and centuries-old debate over whether religious music should be enjoyed as music, a growing faction felt that Mengelberg’s interpretations were over-romantic and heavy (he once had 1,650 performers in all), with an ‘empty virtuosity’ that occluded the spiritual message. Mengelberg was Catholic; you could reasonably liken his performances to an overdecorated Catholic church. Many Protestants felt strongly that the piece should only be performed in a church, on Good Friday. An opposition movement was born, and in 1921 the Netherlands Bach Society (Nederlandse Bachvereniging) was founded with the aim of making the spirit of Bach’s religious music ‘speak as purely as possible’. Their first St Matthew Passion was on Good Friday in 1922, in the Grote Kerk in Naarden. Now there were two camps, and both ‘types’ of performances continued to proliferate.

Then came World War II and the occupation. One could be forgiven for thinking that the Dutch might have stopped putting on or attending a long oratorio by a German composer, sung in German. And the piece’s anti-Semitic undertone would not have gone unnoticed, especially once the atrocities began. But the Passion performances only seemed to offer solace and hope, and to bring people together. The piece is now a ‘civic ritual’ all over the country. Good Friday in Naarden is the one to see and be seen at, especially for government dignitaries – it’s often sold out a year in advance.

The 1960s saw the Early Music revolution, a movement committed (not entirely unlike Mengelberg’s detractors) to performing Renaissance and Baroque music in the way the composers intended. It made classical music cool, adding a younger, ‘hipper’ audience. Today orchestras including the Bach Society playing ‘authentic’ instruments or copies have joined the mainstream, alongside performances by modern orchestras playing modern instruments.

The Netherlands has a strong choral tradition and consequently, many choirs. Most vocal music works best in its original language, and the German language is familiar to people on both sides of the conductor here. The St Matthew Passion is so much a part of choral repertoire here that many choirs give multiple performances every year. One particular for-profit outfit crams over 35 into the season, sometimes two a day, and even one on Easter Sunday (my husband comments, ‘Luther would be somersaulting in his grave!’).

The Netherlands has a strong choral tradition and consequently, many choirs. Most vocal music works best in its original language, and the German language is familiar to people on both sides of the conductor here. The St Matthew Passion is so much a part of choral repertoire here that many choirs give multiple performances every year. One particular for-profit outfit crams over 35 into the season, sometimes two a day, and even one on Easter Sunday (my husband comments, ‘Luther would be somersaulting in his grave!’).

I’ve sung it many times (both choir 1 and 2), and during the 1990s I toured with it in the Netherlands, Belgium, France and Israel. Eight performances in ten days was exhausting. I think it’s a masterpiece and fun to perform, although personally I find the chorales ponderous, especially if the conductor is milking them for meaning.

If you haven’t ever attended one, I do recommend it (trigger warning: contains descriptions of graphic violence). It’s so good that one Prof. Luth of Groningen said, ‘even mediocre performances of it are impressive’. The Bach Society’s will be excellent and you can look for tickets here (full disclosure time: my husband is one of their singers) but there are many more everywhere. Happy Easter!

|

Blog post by: Anne Hodgkinson Website: www.rosettastonetranslations.nl Blog: www.bootsandbowtie.com |

By Cristina Vizcaíno, 5 March 2025

In our fast-paced, 24/7 connected world, journalism is changing at a dizzying speed. With the ‘silent death’ of print media in favour of digital platforms and social media, both the way news is produced and how audiences consume it have transformed dramatically. Today’s journalists face new challenges but also exciting opportunities. To understand this shifting landscape, it’s important to explore the essential skills journalists need, the obstacles they encounter, and the broader trends reshaping the industry.

Truthfulness, accuracy, and keeping the public informed. This is what, at its heart, journalism is. While these core values have survived the passage of time, the tools and skills journalists use to carry out this mission have evolved significantly. Nowadays, journalists need a blend of traditional skills, such as investigative research, and new skills, such as digital literacy and multimedia storytelling.

Investigative research is the essence of journalism. With misinformation spreading like a wildfire, often aided by social media, it is crucial to have an ability to dig deep, verify facts, and uncover the truth. Journalists use both traditional methods and modern tools, like online databases and expert interviews, to cut through the noise of ‘fake news’. Critical thinking is equally essential, enabling journalists to deal with complex issues, identify bias and ask insightful questions that lead to fair, accurate reporting.

Also important is the ability to tell clear, engaging stories across various platforms. From ‘short and sweet’ 280-character tweets to in-depth feature articles or video reports, today’s journalists must know how to survive in digital ecosystems and adapt their storytelling to different formats. While writing remains central, multimedia storytelling is essential for engagement, requiring journalists to create interactive content that captures and retains audiences’ attention. Digital literacy has thus become necessary. Journalists need to be comfortable with a range of digital tools, from content management systems (CMS) to social media platforms like X, Facebook and Instagram. They must understand how to use these tools effectively to reach their audience, optimize content for search engines (SEO), and analyse audience engagement data.

Despite its crucial role in society, journalism faces significant challenges. Financial pressures from declining print media and the rise of advertisement technologies have made it difficult for many media organizations to remain profitable, leading to layoffs and fewer resources made available for investigative reporting. In response, some media companies are exploring alternative funding methods, such as subscriptions or non-profit support. Press freedom is also under threat in many regions, with journalists facing legal harassment, physical violence, and even self-censorship in countries where the media is free. Furthermore, mental health and burnout are growing concerns as journalists grapple with tight deadlines, distressing events, and constant news cycles.

The rise of citizen journalism presents both challenges and opportunities. Thanks to smartphones and social media, almost anyone can report on events, democratizing information and bringing attention to human-interest stories that might otherwise go unnoticed. However, this also blurs the line between professional and amateur reporting. Journalists are trained to uphold ethical standards, while citizen journalists often lack formal training. The real challenge lies in ensuring the credibility of sources amidst the unverified, amateur content. For example, witnessing the role of misinformation during the Valencia floods in Spain last November has been harrowing. To protect the public’s trust and safety, it’s more important than ever for journalists to uphold high standards of accuracy and integrity. I remember when tweeting first became popular, and people could share whatever they wanted. Now, many people treat tweets as if they’re factual truths, and it often feels like anyone can act as a journalist without being held accountable to any integrity standards.

As technology advances, multimedia content such as videos, podcasts and interactive features has become increasingly popular, especially among younger audiences. The shift to digital platforms has transformed how news is created and consumed. Journalists now use diverse formats, including documentaries, audio stories and visual material, to provide deeper, more engaging reporting. Those who adapt their storytelling to fit each platform will be more successful in capturing audience attention. Social media, while offering opportunities for direct engagement, also presents challenges. Algorithms often prioritize sensational stories, making it harder for balanced reporting to gain traction. Journalists must be cautious not to contribute to the spread of misinformation.

In this new era of technology, the growing importance of data-driven journalism and artificial intelligence cannot be overstated. Journalists can now use big data to identify trends and gain a better understanding of complex issues, while AI assists with data processing and even handles some repetitive tasks through automation.

Journalism is at a turning point. To journalists, it might feel like it’s always been this way, with constant change and new challenges. The profession is constantly evolving, often feeling more like a calling than just a job. Despite the rise of new technologies and fast-changing trends, core skills like research, storytelling, integrity and adaptability remain unchanged. While challenges persist, opportunities are emerging in multimedia storytelling, data journalism, and combating misinformation across social media. As long as journalists continue to adapt, their commitment to truth and public service will ensure that journalism remains vital to healthy modern societies.

As a journalist, a reader, or simply as a citizen, it's important to ask ourselves: ‘How do I consume news? Is it reliable and does it make sense to me? Are the sources trustworthy, or could they be influenced by personal or institutional biases? Am I engaging with news in a way that encourages critical thinking and helps me stay informed, or am I just accepting what aligns with my existing beliefs?’ In a world where misinformation spreads so easily, the way we consume news not only shapes our understanding of events but it also influences the wider conversation in society.

|

Blog post by: Cristina Vizcaíno LinkedIn: cvizcainod |